Types of Glaucoma

The Clinical Varieties of Glaucoma

- Primary (idiopathic) or Secondary (associated with some other ocular or systemic conditions).

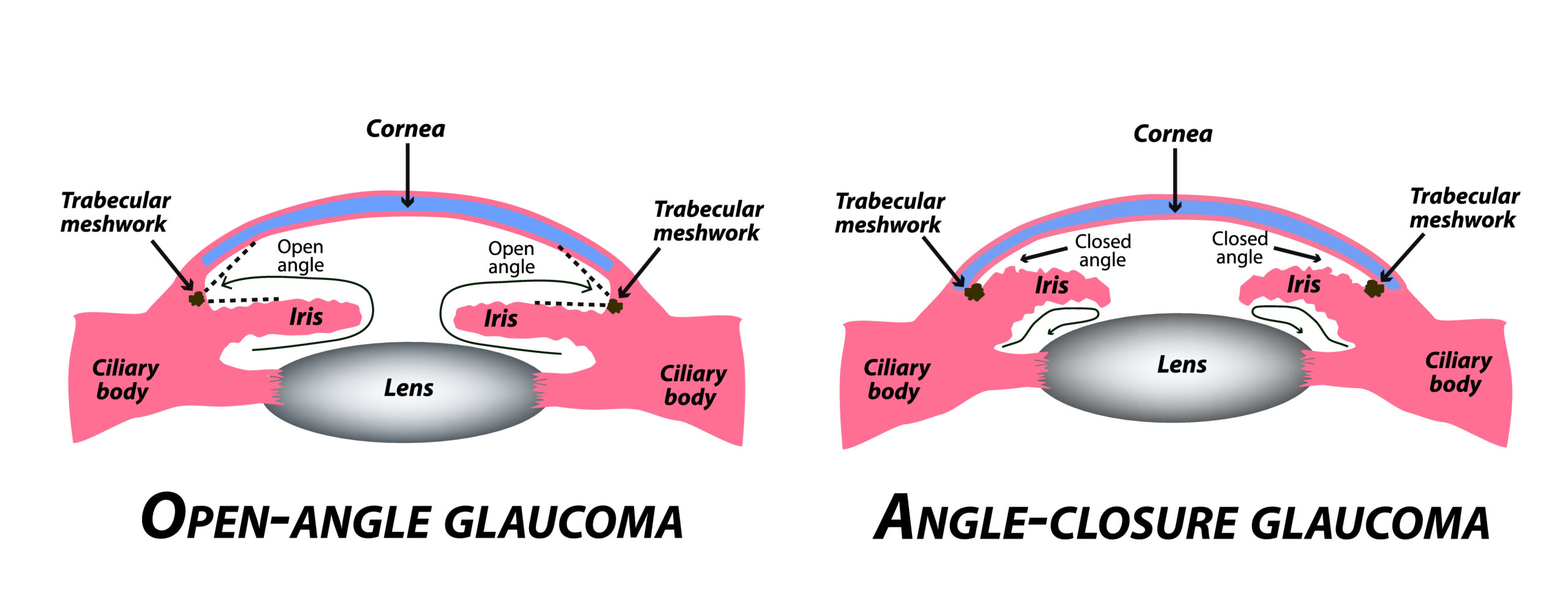

- The state of the anterior chamber angle: open-angle (open access of the out-flowing aqueous humor to trabecular meshwork) or closed-angle (the trabecular meshwork is blocked by the opposition of the peripheral iris).

- Chronicity: acute or chronic. The vast majority of glaucomas are chronic.

Although most glaucoma patients have the primary open-angle type, some 50 different varieties of secondary glaucoma have been described. In general, these are not caused by dysfunction of the trabecular meshwork, but rather by some other ocular or systemic disorders such as inflammation, fragile new blood vessels in the eye, birth defects, ocular trauma or tumors. Although the appropriate diagnosis of unusual secondary glaucoma can make the difference between sight preservation and blindness, most secondary glaucoma is sufficiently uncommon to fall exclusively within the ken of the glaucoma sub-specialist.

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

The vast majority of glaucoma patients have primary open-angle glaucoma. These patients manifest a chronic, idiopathic disease associated with progressive degeneration of the anterior optic nerve, known as glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Although elevated intraocular pressure is an important causative risk factor, only half of the 2 to 3 million North Americans with glaucoma will manifest elevated intraocular pressure at a single measurement. Therefore, measurement of intraocular pressure alone is a poor screening technique for glaucoma. Like most biologic parameters, eye pressure fluctuates throughout the day and varies with other influences, including hydration, sleep, blood pressure, and body position. With multiple measurements at different testing sessions, most, but not all of these glaucoma subjects, will eventually exhibit elevated intraocular pressure at least part of the time.

The rise in intraocular pressure associated with primary open-angle glaucoma derives not from a visible obstruction of the trabecular meshwork, but rather from cellular dysfunction of the trabecular meshwork tissue, which leads to increased aqueous humor outflow resistance. Risk factors for primary open-angle glaucoma include family history, corticosteroid sensitivity, myopia, African-American race, systemic high blood pressure, high intraocular pressure, diabetes, and age. In addition to these risk factors, early age of onset of disease and poor compliance with a medical regimen and physician visits are associated with a worse prognosis.

As mentioned above, some patients with progressive optic nerve damage characteristic of glaucoma never manifest intraocular pressures above the statistically normal range. These patients are commonly diagnosed with”low-pressure glaucoma,” “low tension glaucoma,” “or normal pressure glaucoma.” While recognizing that non-pressure risk factors may play a stronger role in these than in their high-pressure counterparts, these patients are managed similarly to those with conventional primary open-angle glaucoma.

Closed Angle Glaucoma

All physicians need to be cognizant of another form of glaucoma, closed-angle or angle-closure glaucoma, which may present acutely or may be silent and chronic. This disorder, quite unrelated to open-angle glaucoma, derives entirely from blockade of the trabecular meshwork by the peripheral iris, either by simple and reversible anatomical apposition or pressing together, of the two tissues or by generally irreversible scarring and adhesion. These irreversible fibrotic adhesions may occur after unrecognized long-standing appositional angle closure (chronic angle-closure glaucoma) or from other ocular conditions, such as uveitis or neovascularization (secondary angle closure glaucomas).

Classically, angle-closure glaucoma is the well known, less common variety of glaucoma that presents acutely with severe eye pain, blurring of vision, colored halos around lights, nausea, and vomiting. Angle-closure usually occurs in the hyperopic (farsighted) eye, which is smaller than the average eye and thus crowds the iris, cornea, lens and anterior chamber angle into a smaller than average space. Eventually, usually in the fifth to sixth decade of life as the lens gradually increases in size with aging, the lens becomes more firmly applied to the pupillary opening through which aqueous humor from the ciliary body must pass.

This obstruction of aqueous humor flow at the pupil, known as a relative pupillary block, eventually becomes clinically significant and traps the aqueous behind the pupil, raising the pressure in the posterior chamber above that in the anterior chamber and driving the iris anteriorly to lie against and block the trabecular meshwork. This trabecular meshwork blockade, or angle-closure, leads to a sudden and dramatic rise of the intraocular pressure from its baseline normal level in the 10-20 mm Hg range to 60 mm Hg or more. This sudden change in pressure leads to swelling of the cornea with blurring, halos, and severe ocular pain from iris ischemia and corneal edema. The pupillary margin of the iris becomes most tightly applied to the lens surface when the pupil is in the mid-dilated position; hence, it is often dilation of the pupil by exposure to stress, darkness, or drugs that precipitate an acute attack.

The immediate treatment of acute angle-closure is directed toward reversal of the pupillary block, usually by moving the pupil with constriction. Ultimately, however, the pupillary block can be reversed and prevented by creating a new aqueous channel with peripheral iridectomy. (see Treatment)

How is Glaucoma Associated with Ocular Trauma?

Glaucoma may develop after ocular trauma. Penetrating injuries to the globe disrupt, or even destroy, intraocular contents and may lead to sustained elevation of intraocular pressure and glaucoma. (see Ocular Trauma) A more subtle, insidious glaucoma may arise from blunt ocular injury or ocular contusion, as occurs when the globe is struck with a fist, ball or another object. Blunt injury temporarily deforms the globe, causing shearing between its internal tissue layers. These shearing forces may tear the insertion of the iris (iridodialysis) or ciliary body (cyclodialysis) from its attachment to the sclera. Most commonly, the fibers of the ciliary muscle that both control accommodation and modulates aqueous humor outflow become detached, leading to the collapse of the trabecular meshwork (known as angle recession) and subsequent secondary glaucoma.

Acutely, the contused eye typically presents with intraocular bleeding (hyphema), and the intraocular pressure may be low, normal, or elevated. Angle recession glaucoma may not manifest for months or even years after the original injury. Treatment of glaucoma from blunt ocular trauma follows a similar protocol to more common open-angle glaucomas, except that these eyes do not respond well to pupil-constricting drops such as pilocarpine because of the damage of the ciliary muscle. Because of the damage to the trabecular meshwork, laser trabeculoplasty is similarly ineffective. Thus, when regular glaucoma drops are ineffective, filtration surgery usually becomes necessary.

What is Pigmentary Glaucoma?

Pigmentary glaucoma is a relatively common secondary glaucoma in young adults and appears to be exclusively an ocular disorder. This disease is relevant because of the potentially severe consequences for young people. Pigmentary glaucoma occurs primarily in young myopic (nearsighted) adults and is more common in males, usually manifesting between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Melanin pigment granules from the iris circulate freely in the aqueous humor, become deposited or entrapped in the surrounding tissues of the cornea, iris, lens, and particularly within the trabecular meshwork. This leads to obstruction of the meshwork, elevation of intraocular pressure, and glaucoma.

This condition may manifest with intermittent visual blurring or dull ocular pain, but like other glaucomas may go unnoticed until a severe visual loss occurs. Vigorous physical activity or pupillary dilation may induce a shower of pigment granules to be released from the iris in these patients, resulting in a transient, acute rise in eye pressure, corneal edema, blurred vision, and ocular pain. Treatment of pigmentary glaucoma is similar to that for primary open-angle glaucoma.

What is Neovascular Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is typically a disease of the middle-aged and the elderly. Thus, its occurrence in children or young adults always raises the question of some associated condition, such as an intraocular tumor. Diabetes mellitus and other vascular disorders are frequently associated with neovascular glaucoma. The devastating consequences of diabetes upon the retina are well known. In addition to retina problems, the diabetic patient may also develop glaucoma as a result of retinal ischemia, known as neovascular glaucoma.

Neovascular glaucoma is one of the most devastating varieties of glaucoma. Just as damage to the small blood vessels of the retina results in the formation of fragile new vessels and bleeding, retinal ischemia may also cause new vessels and scarring in the front part of the eye. It is believed that an angiogenic factor is produced by the ischemic retina, leading to new vessel formation inside the eye.

Unfortunately, these vessels are abnormal and may cause a variety of vision-threatening problems. Neovascular glaucoma derives from the proliferation of fragile new vessels on the iris (rubeosis irides) and into the anterior chamber angle. The trabecular meshwork provides a fertile template for neovascular growth, which ultimately leads to a complete blockage of aqueous humor outflow, marked elevation of intraocular pressure, and severe, often painful, blinding glaucoma.

This process can also follow other vascular conditions associated with retinal ischemia, including occlusion of the central retinal vein, occlusion of the central retinal artery, and even carotid artery disease without known damage to the eye. Treatment of neovascular glaucoma is multifaceted and involves diligent systemic management of related vascular disease, treatment of retinal ischemia, and lowering of the intraocular pressure with medical and often surgical therapy.

What is Congenital Glaucoma?

Although glaucoma is commonly associated with an adult, even the elderly, patients, childhood or infantile glaucomas also exist. The most common, primary congenital open-angle glaucoma occurs in children without other identifiable abnormalities. Most cases become evident in the first year of life and often are discovered in the newborn nursery or during the first few weeks of life. The exact cause of infantile glaucoma is unknown but appears related to a delay in the development of the aqueous humor outflow channels.

Infants with congenital glaucoma present with photophobia (shyness to light), epiphora (tearing) and blepharospasm (blinking or squeezing the eyelids). The principal clinical sign is an enlarged cornea, often bilaterally. As the disorder advances, the cornea becomes edematous and appears cloudy. The appearance of an enlarged cloudy cornea in an infant essentially makes the diagnosis of congenital glaucoma and is obvious to casual penlight examination. Prompt referral to an ophthalmologist for intervention can make the difference between sight and permanent blindness.

Various forms of developmental glaucoma may also be associated with congenital malformations of the anterior chamber angle. Common is the Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome associated with dental, facial and other midline developmental abnormalities, adhesions between the cornea and iris, and glaucoma. Aniridia is a bilateral congenital absence of iris that may be inherited by autosomal dominant transmission or may occur spontaneously. These latter, spontaneous cases, may be associated with kidney tumors or other anomalies of the genito-urinary system. Glaucoma with aniridia usually occurs in early to mid-childhood and is not typically associated with enlarged corneas.